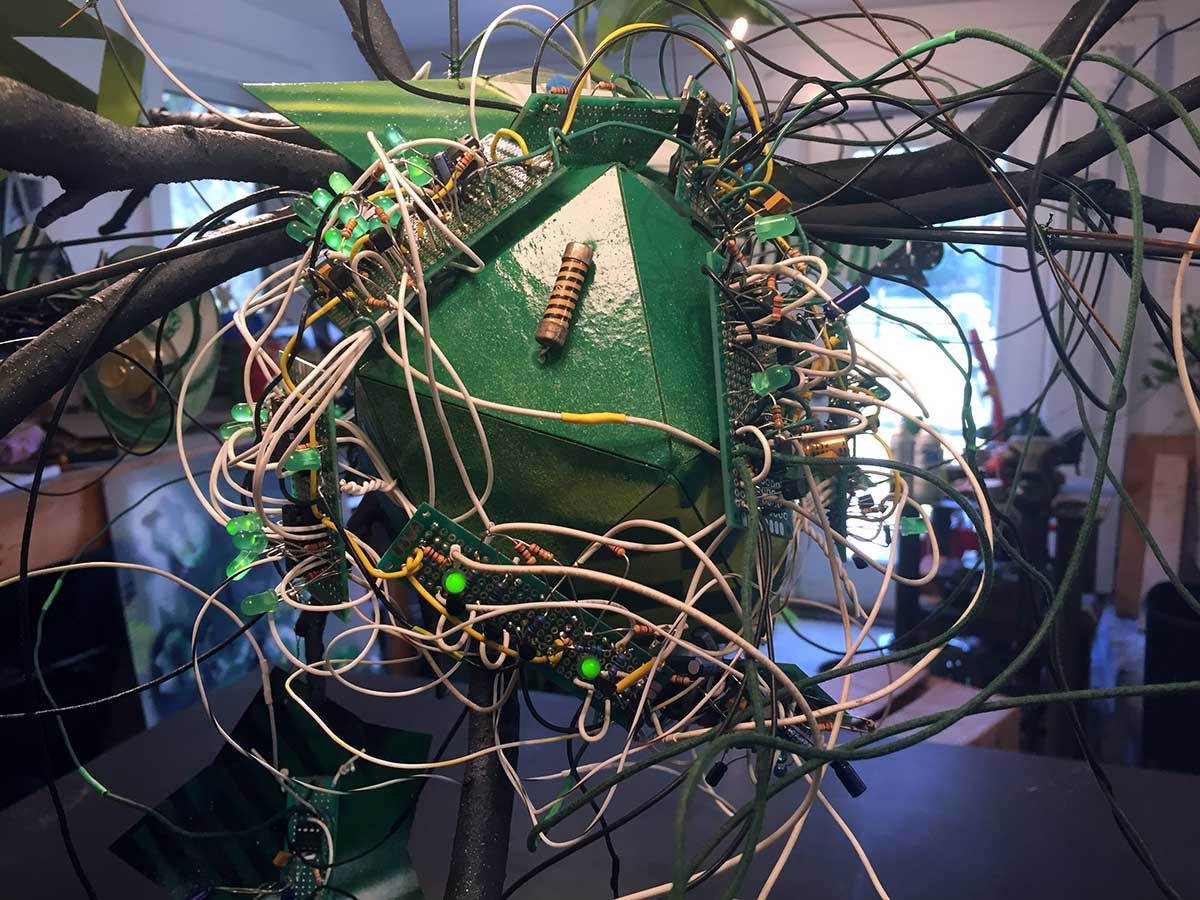

New footage of my Moth Electrolier from 2019

In this sculpture, analog electronic circuits generate patterns of animated light that mimic the flight trails of moths around a bulb. The circuits are made with a series of oscillators connected together to form pseudorandom patterns, and these patterns are used to clock shift registers. This is why the animation occasionally "flutters" before continuing along the sequential trail. The wings of the moths are dyed velvet that were embroidered with an old industrial machine according custom CAD files. The translucent plastic sphere is laser cut acrylic that was heated and shaped into spiral patterns. The sculpture attempts to depict living nature in all of its magical, electrical movement as well as its delicate fragility. As electronic technology increasingly shapes our built environment, it is harder to distinguish between biological and machine intelligence. The construction of circuits that mimic life-like behaviors is part of my "electronic naturalism" practice to demonstrate just how similar circuits and living organisms can be -- without any code or recording to inform the behavior, just the physical assembly of electronic devices that vibrate when exposed to voltage. This and several other sculptures from the same time period (Birds at My Feeder and Electrolier (Summer Night)) were created during the same time as I published my Hackaday project, "Hacking Nature's Musicians." A diary with process images and associated schematics can be found on the following pages:

hackaday.io/project/161443-hacking-natures-musicians

hackaday.io/project/163201-electronic-sculpture

Moth Electrolier and Birds at My Feeder are a celebration (and demonstration) of the open source hardware and Makerspace movements that were happening around this time in history. I used various unusual techniques to create these works, including an old embroidery machine, laser cutter, thermoformer, Blender (open source 3D modeling software), and a bricolage of electronic hardware techniques from my earliest foray into printed circuit board design. I would like to thank NovaLabs Makerspace (formerly in Reston, VA) for the various equipment and education that I used to make sculptures during this time.